You don’t have to be an electronic music head to understand its sound’s meditative grip. Built on repetition and the pull of rhythm, whether through a heavy bassline or a leafy atmospheric texture, there’s this immersion it creates, that trance-like state, that defies all laws of our somatic perception.

However, we could argue that electronic music goes far beyond sound’s ability to suspend reality or pull you into a dance-off. Technically, it wouldn’t be what it is today without its visual counterpart. The visual arts in electronic music are as essential as they are branched into two separate concepts. One side of the spectrum acting as artists creating visuals onstage, and the other adopting the role as visual architects for immersive experiences.

This duality of audiovisual art seems to become more central to the scene every year. And it’s not a slight, amicable co-existence. The two sides of the most celebrated music scene have found a way to agree to disagree in the most elegant way possible.

On one side, top acts defend their identity in front of astonishing digital art pieces, solidifying their god-like status as they construct their brand. On the other side, artists find anonymity—the opposite of individual stardom. They find a curiously radical antithesis by deconstructing what a brand represents.

Meanwhile, festivals have eagerly hopped aboard the immersive experiment. Events from around the globe, including this past month’s Amsterdam Dance Event (ADE) and MIRA Festival, are keen to feature the immersive pioneers who are completely stripping away the stage and conventional performance. It might be daring to call them artistic anarchists, but they clearly show how crucial the visual language has become in the electronic music scene.

Come to think of it, visuals were first introduced as a mere ornamental advantage. Now, they have fully come into their own, recognized for their essential and equal force in shaping the whole electronic experience.

Spectrum One: the visual artists behind a show

We could get carried away with this one. As no one just drops a set in a dark room under a constellation of lab lights anymore. If they ever did. We’re talking about back in the day, when sound engineers were navigating the Avolite Titan by intuition to get people’s feet moving. But now, we have pivoted our last move into what seems like the peak of monumental visual performances.

The scene has come a long way in the past 60 years. From simple gear fiddling to monolithic shows, visual artists are finally getting the recognition they deserve. The electronic music scene is a huge player in this. For example, take Smith & Lyall, who warp Chemical Brothers sets into psychedelic topographies that feel like alternate dimensions you could get lost in. Or there’s Alessio de Vecchi, whose Anyma visuals scare the living light out of you. Their colossally magnetic screens feel almost intimidating, amplifying every human existence into pure adrenaline and excitement.

This magnificence, however, comes at a cost. It establishes a tyranny of the spectacle, which strengthens the star’s brand and creates an economic barrier for the underground. Yet, we shouldn’t dismiss this high-budget spectrum as just a commercial display. To do so would be to miss its most crucial contradiction.

Because these acts command the biggest stages, their visuals can also be used as a powerful tool to spread political awareness directly to massive audiences. For instance, United Visual Artists turns a Massive Attack performance into an outstanding display of global calamities. They use a data-driven digital show to weaponize their popularity and spread awareness. This is the positive paradox: the huge event budget that makes the performance possible also grants them a globally visible platform for powerful sociopolitical display. However, this effect is, ironically, transactional. The noble act simultaneously stamps their brand with this activist identity.

Speaking of identity, think Jamie Hewlett, who has long become the master of combining illustration and animation for the Gorillaz shows. His pieces carry a different kind of weight. They take your current conscience and let you fall into step with the characters accompanying Damon onstage – a whole different strut from our own reality. His artwork is a signature Gorrilaz recognition now. And Pfadfinderei, shaping Moderat shows with their signature kinetic delirium, prove that visual design can be unexpectedly random yet mesmerising all at once.

So, there’s no simple way to give a set the light it deserves. Every art form eventually becomes a product, and we can’t ignore the human drive to push a concept to its limit. In this case, that means moving toward the biggest, most outstanding show, which are truly breathtaking to witness.

Having said that, our signature urge to return to the roots is surprisingly powerful. Look at parties like Torax; eight-hour afternoon techno marathons inside Barcelona’s most iconic club, which embrace near-total darkness. They let the absence of light immerse attendees in their own visual interpretation, appreciating the core of underground electronic music. But even there, they play with minimal light.

Since the beginning of VJing, there has always been this alchemy: lights dancing in time with the music, changing the atmosphere to enhance the spectator’s experience. Whatever the argument, it’s safe to say that what started as some basement experiments with sync boxes, 16mm projectors, and VHS tapes has now mutated into one of electronic music’s most respected and provocative art forms.

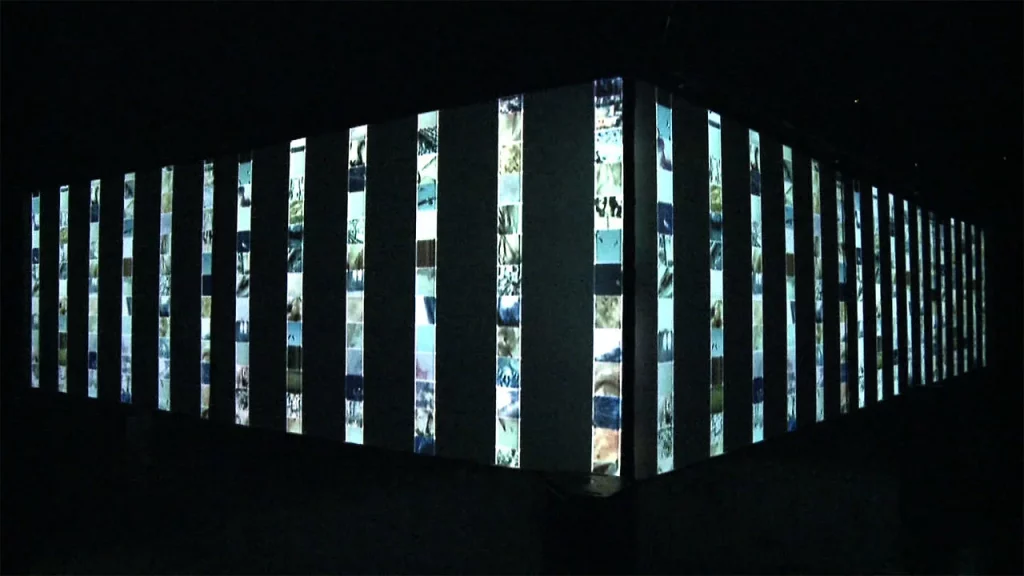

Spectrum Two: the immersive pioneers

While the first type of show impresses from the stage, this second spectrum seeks to dissolve the hierarchy completely. This concept grew popular long ago from the urge to push boundaries and decentralize the spotlight. It invites attendees to become essential parts of the installation itself. By spilling electronic music beyond the DJ booth, artists step down from the pedestal to become a mere catalyst for the art. Basically, it asks us to go against intuition: the concept does not aim to stand out. Instead, it aims to find meaning in deconstructing the trademarked frame.

Some would label these spaces a gimmick, or, alienating loss of mystery. But, this dismissal could distract from the project’s true ambition. It is an impulse that traces back to the birth of “musique concrète” in the ’40s. When pioneers like Pierre Schaeffer began manipulating recorded sounds and treating them as raw materials for composition.

This leads us to the birth of anti-spectacle shows, where musicians detached sound from its context and began experimenting with random loops and eccentric rhythms—a signature Brian Eno move. This fostered a sense of disorientation toward a different kind of music. Acting as a philosophical precursor to debranding, this simple shift of interest moves the focus from the person creating the art to what the art is actually doing to us.

What started as an exploration of tape loops consequently opened doors to the idea of multisensory experiences. It fuses the importance of visuals into the immersive mix, either enhancing an existing ambiance or changing it entirely.

For instance, Max Cooper bends perception with multi-layered audiovisual journeys, mapping neurons, nature, and time itself into living soundscapes. An Irish former computational biologist, he took the leap into exploring the significance of reality perception through sound and visual documentation. Or Japanese artist Daito Manabe, who digitally investigates movement, light, and electronics in a kinetic dialogue between body and space.

This doesnt retract from the alienating aspect of the show. Same way Classical music music was the correct Western form of musical performance for years until rock decipherers took over the stage in the most ungodly manner. Some loved it, some questioned it. The primal comfort of the conventional electronic music dance floor is always going to be the preference for certain people. But here, audiovisual experiences are going to be a curious relief for others.

Take a dive into the work of Lolo & Sosaku, who create both live shows and ongoing installations. They experiment with machinery, robots, and algorithmic patterns that lock into desired rhythms after the manipulation of certain gadgets. This is a live art form that has left some feeling cleansed and others slightly traumatized. Also, look at Tokyo-based Ryoichi Kurokawa, who pulls texture into digital landscapes, accompanied by his own distorted music compositions. “Sense” won’t be your first thought, as the approach is completely different.

Then there are spaces curated by Allapop, Noemi Buchi, and Carlos Martorell, who merge material and body, projection, and sound into terrains you can wander through. Leading digital art festivals like Mutek, Mira, Semibreve, Amsterdam Dance Event (ADE), and LEV show how far immersive electronic art is stretching. The analog world may precede the digital one, but the way electronic manipulation is defining art today is nothing short of transformative.

From onstage screens, LED modulations to digital urban interpretations using the natural performance of sound. These two worlds are in a constant state of convergence. The fact that visual artwork has migrated from a mere sound companion to almost a central part of the evolving electronic music scene, is no small statement.

Case be made, we find ourselves at the height of digital creativity but, most importantly, of a radical attempt to go break loose from artistic repression in a world obsessed with brand and identity. Up until now, visual artists have come across targets one could only wish for. So, as we stand here out of genuine artistic curiosity or simply to keep up with a trend that technology makes irresistible, in all manners -detraction or contribution – the visuals in electronic music are teetering on the brink of their own evolution.